German by birth and of Turkish origin, director Fatih Akin has coherently and beautifully squeezed six big lives into a mosaic that connects Bremen, Istanbul, Hamburg and Trabzon in his latest film, The Edge of Heaven.

German by birth and of Turkish origin, director Fatih Akin has coherently and beautifully squeezed six big lives into a mosaic that connects Bremen, Istanbul, Hamburg and Trabzon in his latest film, The Edge of Heaven.

Three-dimensional characters shot in wonderfully tangible ways make this film a quiet emotional ride. A short way into the film, before we have even been introduced to her, Yeter’s death is announced. Yeter, a prostitute who sends money home to her daughter in Turkey, moves in with one of her clients, the elderly Ali. His son Nejat is slightly horrified by this change in living arrangements, but warms to Yeter.

After Yeter’s death Nejat moves to Istanbul to try and track down Ayten, Yeter’s daughter. And so “a Turkish professor of German from Germany ends up in a German bookshop in Turkey” – a symbolic piece of dialogue which encapsulates the ease with which the film and the characters bump across cultural and geographic divisions.

Ayten is a fighter with an armed Turkish resistance group who has fled to Germany. She is befriended and then loved by student Lotte who in the end will do anything to help not only Ayten but the resistance as well, after Ayten is deported back to Turkey. The audience is warned of Lotte’s death at the beginning of the second act, again like Yeter before she appears on screen. Lotte’s death leads her mother, comfy middle class hippy Susannah, to seek out Lotte and her cause in Istanbul.

This plot, which relies on the coincidental interweaving of these lives, is tightly edited into a well-paced narrative. Each character has enough space to develop a credible relation to the plot but little back story. It is refreshing to let the viewer wonder how they all got to where they are without having any tortuous exposition ritual to fill in all the missing blanks.

A film that brings together Turkish and German in this way innately has a political edge. Ayten is imprisoned in Turkey for her membership of the group and while in Germany she clashes with Susannah who sees her only as a person who wants to fight. Deportations, Turkish law and whether Turkey’s membership of the EU will make a difference are all present. The openings of the first two acts show political protest, the first in Germany and the second in Turkey. What makes this film engaging is that these incidents aren’t separated or above the story or the characters. They are a part of it.

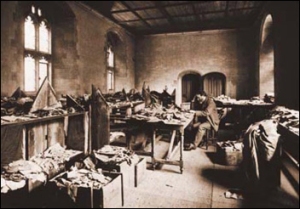

In the opening shot a young man strolls across a square in Budapest, his yellow-starred coat flapping in the wind. The camera focuses on the star, giving a foreboding sense of the horror to come. From the start we know where we are, we know the story. The grotesque conclusions to the Nazis’ eugenics programme are not a new subject for cinema, but this debut is visually stunning and emotionally powerful.

In the opening shot a young man strolls across a square in Budapest, his yellow-starred coat flapping in the wind. The camera focuses on the star, giving a foreboding sense of the horror to come. From the start we know where we are, we know the story. The grotesque conclusions to the Nazis’ eugenics programme are not a new subject for cinema, but this debut is visually stunning and emotionally powerful.